Munich

|

|

"MŁnchen Mag Dich" |

On all controversial subjects, much remains to be said.

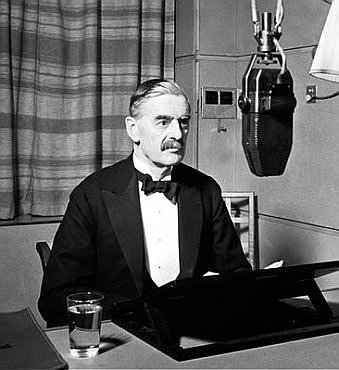

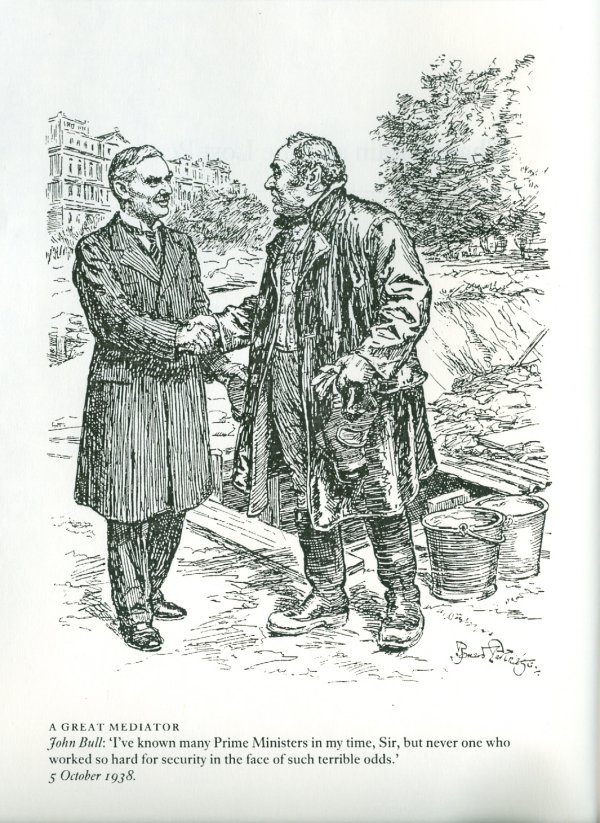

The city of MŁnchen is synonymous in the minds of many with the well-meaning man, Chamberlain, whose name will forever be associated with the infamy of appeasing a diabolical dictator.

Neville Chamberlain, who became Prime Minister in 1937, had wide experience in politics and was a popular choice for the position at the time. Neville was an easy man to respect but a difficult one to like. He was high-handed, imperious, intolerant of and impatient with any who dared disagree with him. Despite his bleating voice and frail, feeble appearance, he was a prime minister who led from the front. He cowed his cabinet, few of whom were prepared to differ with his decisions.

Chamberlain, who knew he was scorned by many, revelled in his unpopularity, which he believed was a reflection of his strong, aggressive leadership. He was less than flattered with his appearance, however, commenting after viewing himself in a film, that he was "pompous, insufferably slow in diction and unspeakably repellent in person." Nevertheless, Chamberlain felt secure, for he had firm authority over the Cabinet and dominated Parliament. His appeal to the country was yet to come.

"Kindred blood should belong to a common empire," railed Hitler and he proceeded to make this happen. Flaunting the terms of the Versailles Treaty, he took his troops into Austria, where to a quarter million madly cheering Austrians in the Heldenplatz (Heroes' Square), he declared that the independant country of Austria would henceforth become the German province of Ostmark.. Having accomplished Anschluss by hauling his homeland into the German Reich, he cast about for another victim to vanquish and his eyes fell upon Czechoslovakia.

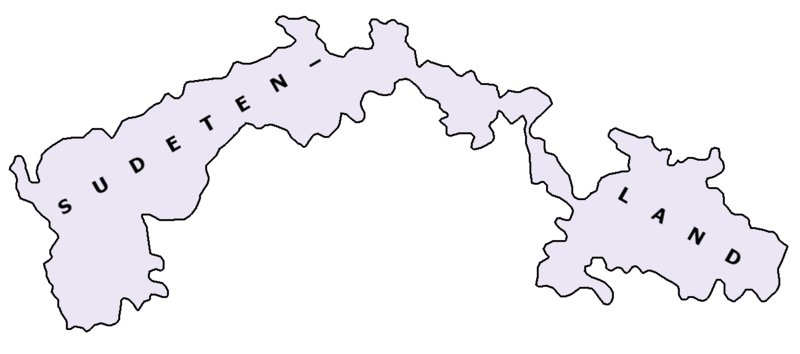

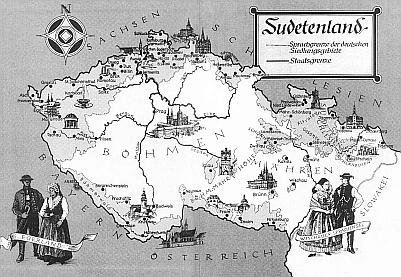

Hitler regularly fostered fantacies of terrible injustices being suffered by Germans living in other countries to justify Nazi aggression. One third of the population of Czechoslovakia was comprised of Germans living in Sudetenland (Southland) and while there were tensions between the two peoples and they had grievances the Czech government should have ameliorated, they were by no means suffering citizens.

Hitler hated "this spearhead in the side of the Fatherland," a crafted country created by victors of WW I from bits and pieces of the fractured empires. As Mussolini pithily pronounced, it was not just Czechoslovakia, but "Czecho-Germano-Polono-Magyaro-Rutheno-Roumano-Slovakia." Hitler, who had hitherto ignored their existence, suddenly decided the Sudentenlanders needed a hero named Hitler to take up the cause he had created for them. Some responded positively to Hitler's posturing. Declaring it his mission to eliminate their misfortunes, he warned the world it could mean war. With chaos waiting in the wings, Europe noted the danger and was daunted.

Lloyd George, one of the country's crafters, had serious misgivings about creating Czechoslovakia, but the persuasive Prime Minister Eduard Benes won the day by promising the Peace Conference to organize the minorities that made up his new country on a cantonal system similar to that of Switzerland. That promise was never fulfilled and Benes created instead a centralized state dominated by the Czechs. This resulted in racial bitterness that was exacerbated by the economic depression in the industrialized area of the country.- Sudetenland,

|

|

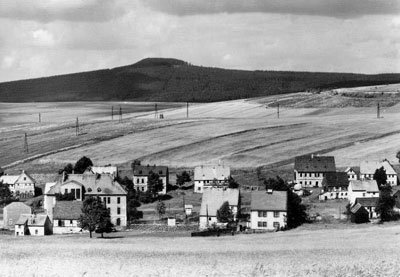

Sudetenland |

The northern fringe of Czechoslovakia contained mountainous approaches and the country's fortifications, so its loss to Germany would leave Czechoslovakia militarily defenceless.

|

|

Czechoslovakia |

Neville despised the French, deeply distrusted the Russians, scorned the Americans and disliked the Germans "who are bullies by nature." The biggest of these bullies had begun to throw his weight around and arbitrarily decided to make changes in the map and makeup of Europe. Someone had to halt Hitler and Neville got the nod.

Britain was woefully unprepared for another devastating war over the fate of a faraway country of which, said Chamberlain, we know little, In a letter to his sister , Hilda, he vented his rage. "Those wretched Germans. I wish them at the bottom of the sea instead of which they are at the top of the land, drat Ďem." He racked his brains "to devise some means of averting a catastrophe." . Determined at almost any cost to avoid a cruel calamity over this crafted country, the creation of which, British leaders agreed was, "highly artificial," Neville implemented Plan Z: a face to face meeting with the Fuhrer himself. Only Neville and Adolf could resolve the dilemma.

Adolf Hitler, was a ridiculously dangerous demagogue" considered capable of any "mad dog act". Neville knew Hitler had dreams of becoming a new Napoleon and that he had mocked him as an Arschloch (arsehole), but he sincerely believed he and he alone could persuade Hitler to forgo fighting and agree simply to accept the Sudetenland pleasantly offered him on a platter, rather than taking it violently by bayonet, bullet and blood.

Hitler's violent outburts were signals to his henchman Henlein to stir up trouble in Czechoslovakia, where. Henlein's rousing, riling words led to rioting in the streets. The Czech government took the troubles in its stride and in measured fashion, managed to settle some things down in Sudetenland. Hitler, however, used the unrest to rage that the government had lost control necessitating armed intervention to stop the strife. War fever became wide spread and the tension was "indescribable." Henlein left for Germany with these parting words, " We wish to live as free Germans."

On the 13 September the British government learned from secret sources, that it was Hitler's avowed intention to invade Czechoslovakia on the 25th of September. He wanted war regardless of the consequences and Neville decided the time had come to implement Plan Z. (Zero Hour)

Other than a few close friends, Neville had told no one of his plan to fly to the Fuhrer. The trip had not been approved by Parliament, nor sanctioned by Cabinet. He informed the King of his plan just before his departure for Germany. Britain's Foreign Minister, Lord Halifax, said it took his breath away. When it became public, the world gasped at a magitude of the mission that captured the its imagination. Summitry today is a common occurrence, but at that time it was an audacious innovation. Newspapers in Prague greeted Zero Hour news negatively, shouting their derision at "the mighty head of the British Empire about to go begging on bended knee to Hitler."

Taken aback by the news, Hitler was gleefully amazed at Chamberlainís appeal. "This reincarnation of some ancient evil," was easily offended by swearing, so his emotional outburst was limited to the mild, "Um Himmel willen." [For Heavenís Sake.] Many wondered why Hitler had agreed to such a meeting. Indoubtedly, it had something to do with this obeisance from no less a leader than the Prime Minister of the mighty British Empire, for which Hitler had always harboured admiration. "Ich war wie vom Donner gerŁhrt"[I was thunderstruck], said Hitler. While the Fuhrer was flattered by this personal appeal, Hitlerís vanity was somewhat vitiated by the slow-down this caused the collision course on which he was bent..

Hitler was informed of the Prime Minister's proposal 9 am on Wednesday 14 September 1938 and by 2:30 p.m. the Fuhrer had responded that he would receive Chamberlain at Hitler's haven in Bertesgaden located at the far eastern part of Germany.and necessitating a longer flight for Neville.

|

|

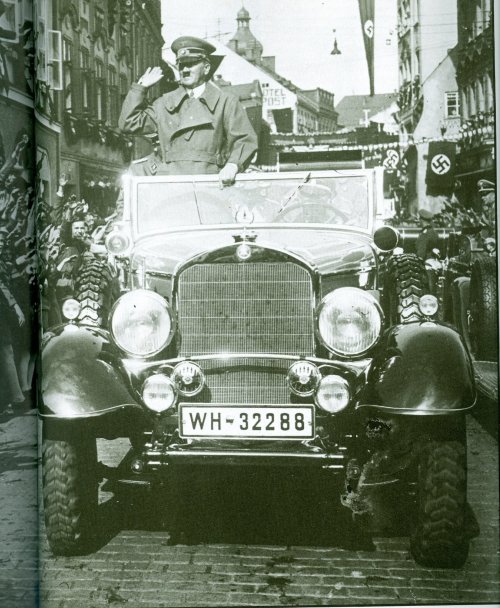

Adolf Hitler |

At 8:25 a.m.on Thursday, 15 September 1938, Chamberlain. arrived at Heston Airport .According to an eye witness, he got a good "send off and take off," for this mano mano meeting with the Fuhrer. The sixty-nine year-old Prime Minister boarded the British Airways twin-engined Lockheed Lodestar for his very first flight on this craft. I

|

|

All Aboard |

|

|

As it heaved, shuddered and shook its way across Europe for nearly seven hours, one wonders as he watched the clouds float by, whether Neville questioned, "Is this worth the risk?" |

|

|

The lengthy trip was to be a stressful strain on the nearly 70-year old man. |

Hilter's insecurity always prevented him from ever being magnanimous, so he did not offer to meet Chamberalin closer than Berchtesgaden at the eastern extremity of Germany. It was 4 p.m. when Neville arrived after having travelled since dawn. In a letter to his sister, Ida, Chamberlain wrote that he "felt quite fresh" during the ride from the airport to the station, where he boarded Hitlerís special train for the trip to Berchtesgaden.

|

|

Berchesgaden from a Cable Car |

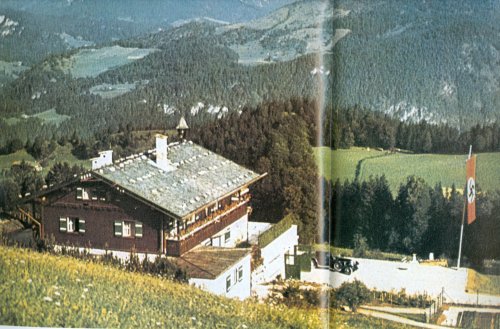

Chamberlain was "delighted with the enthusiastic welcome of the crowds all the way to the station." He was also impressed by Hitlerís alpine residence with its breathtakingly beautiful scenery. Unfortunately, the sky darkened, it started to rain and clouds obscured the mountains.

Protected by hundreds of armed guards, Hitler's haven at Obersalzburg in Berchtesgaden near the Austrian-Bavarian border, had a pastoral beauty and serene atmosphere in the wooded Bavarian Alps that was said to revitalize the Fuhrer.

|

|

Hitler's Berghof |

|

|

Hitler's Berghof |

|

|

Neville is greeted by Adolf and friends. |

|

|

The intimidating presence of General Keital at Hitler's side was not lost on Chamberlain. |

|

|

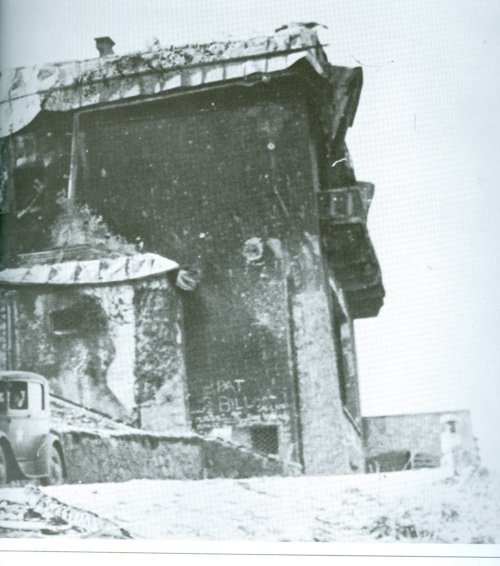

Allied raids made ruins of the Berghof |

|

|

Shane Atop Ruins of the Reich's Regime |

|

|

Nazi Ruins viewed by Shane |

The salon at the Berghof, Hitler's mountain retreat above Obersalzberg in the Bavarian Alps, was a large room, sparcely furnished with oversized furniture. The sidebord was ten feet high by eighteen feet long; a twenty-foot-long table; a massive clock with a bronze eagle; a grand chest concealing phonograph speakers; paintings by Titian and members of his school and a landscape of ancient Rome; a huge fireplace with red stuffed chairs before it and an uncomfortable low sofa that seated eight abreast. An immense picture window could be mechanicallly raised or lowered and gave a view of awesome chasms and peaks beyond.

Chamberlain described to Ida the scene at the Berghof. "Half way down the broad outdoor stairway stood the Fuhrer, bareheaded and dressed in a khaki-coloured coat of broadcloth with a red armlet and a swastika on it and the military cross on his breast. He wore black trousers such as we wear in the evening and black, patent-leather, laced up shoes. His hair is brown, not black, his eyes blue, his expression rather disagreeable in repose and altogether he looks entirely undistinguished. You would never notice him in a crowd and would take him for the house painter he was." Later Chamberlain felt freer to be more frank and called Hitler "the commonest little dog" he had ever met.

|

|

Hitler and Neville take tea. |

"We sat down - Hitler, Schmidt and myself. Hitler seemed very shy and his features did not relax, while I endeavoured to find small talk."

" I have often heard of this room, but it is much larger than I expected.""It is you who have big rooms in England."

"You must come and see them some time."

"I should be received with demonstrations of disapproval."

"Well, perhaps it would be wise to choose the moment."

At Chamberlain's wry comment, "Hitler permitted himself the shadow of a smile."

Chamberlain stared through the huge window and commented on the dazzling splendor. Hitler remarked it was unfortunate the rainy weather prevented him getting the best view.

When the finished tea, Hitler inquired what procedure Chamberlain proposed. Chamberlain suggested if they have a tete-a-tete. Hitler walked up stairs, passing through a long room containing pictures of nudes His own room was completely bare of ornament. It contained only a stove, a small table with 2 bottles of mineral water (not offered to Chamberlain), three chairs and a sofa. There they sat and talked for three hours.

|

|

Hitler, his interpreter, Schmidt and Chamberlain |

Hitler outlined his views on racial unity and his determination to return to the Reich all Germans. Having merged seven million Austrians with Germany, he fixed his face fanatically on Czechoslovakia's three million, German-speaking Sudetens. Chamberlain halted his harangue by inquiring whether this was his only demand. Hitler said when this was achieved and all the other minorities had seceded from Czechoslovakia, what remained was of no interest to him. Schmidtís version of this was somewhat different: "Czechoslovakia would, in any case, cease to exist after a time."

Despite Chamberlainís obliging attitude, Hitler glared as he declared he would demand nothing less than the annexation of the Sudeten territory. "I am determined to settle it; I donít care whether or not there is a world war." To the shocked astonishment of Schmidt, - no one in the Reich would ever dare to interrupt der Fuhrer - Chamberlain interjected angrily, "If I understand you correctly then, youíre determined in any event to proceed against the Czechs. Why have you had me coming to Berctesgaden at all? Apparently, itís all pointless." Unless Hitler had something further to suggest, Chamberlain said, it seemed nothing else could be done.

Tense silence greeted this outburst and then to Schmidtís even greater incredulity, Hitler retreated. His whole demeanor changed and in a calm, quiet voice, he said that if Chamberlain could assure him that the British Government accepted the principle of self-determination for the Sudetendeutsche, he was prepared to discuss how it might be accomplished. Seizing at Hitlerís seemingly conciliatory change of attitude, Chamberlain quickly assured Adolf that he personally could see no reason why the Sudeten Germans should not be in the Reich. However, consultations with others would be necessary, after which he agreed to return for a further meeting. Hitler, feigning regret that the Prime Minister had to make two trips, graciously agreed to meet him halfway near Cologne.

Finally home at Heston at 5:30 in the afternoon on Friday 16th, Neville was driven to Downing Street where he arrived at 6:20 and had a meeting with his Ministera at 6:30. He gave his impressions of their meeting and said he thought he had Hitler for the moment.

The next few days were spent applying pressure on the Czechs to acquiesce to their countryís dismemberment. President Benes, whom Churchill called ĎBeansí, was awakened from sleep to receive the Anglo-French ultimatum: the Sudetenland must be annexed to Germany. He said he had no alternative, but to submit to pressure. Not so five years earlier,when Benes had publicly declared, "No country could be forced by anyone to revise its frontiers, and that anyone who attempted it in the case of Czechoslovakia would have to bring an army along." At that time he believed his forces would be bolstered by those of other democracies if his country was threatened. France, in fact, had signed an agreement to do just that. He learned rather late that, as Hitler observed in Mein Kampf, "An alliance whose object does not include the intention to fight is meaningless." To compensate Benes for being willing sacrifice so much of his country, his so-called allies, Britain and France, pledged to defend from further German aggression, what was left of his country. Their word and warrant were worthless.

|

|

Chamberlain leaves Heston on a Lockheed 14 Super Electra on 22 September 1938 bound for Cologne and his second meeting with der Fuhrer. |

Chamberlain was welcomed at Cologne airport by a galaxy of dignitaries and his passage through streets decorated with swastikas and Union Jacks was greeted by thousands of cheering, joyful Germans. On Thursday 22 September, Chamberlain and Hitler met at Godesberg, a quiet, spa-resort town on the Rhine just outside Bonn.

|

|

Bad Godesberg, located along the hills and cliffs of the west bank of the Rhine river in west central Germany. |

|

|

The Dreesen Hotel, September 1938 |

|

|

The Dreesen Hotel 2011 |

The Dreesen Hotel is situated along one of the most beautiful parts of the River Rhine in Bad Godesberg on the outskirts of Bonn. The site of the second meeting of Chamberlain and Hitler, it was one of Adolf's favourite hotels.

|

|

Neville and Adolf entering the Dreesen Hotel |

|

|

Neville and Adolf in the Dreesen Hotel |

Chamberlain was in fine fettle as he entered the hotel, for he believed he had secured a deal that would give Hitler what he wanted without the shedding of a drop of anyone's blood. He nnounced proudly at their meeting that he had gotten agreement to the terms from the British and French governments and had forced the Czechs to accept them by an Anglo-French ultimatum. An exaltant Chamberlain announced that the Sudetendeutsche districts would be transferred to the Reich and where no satisfactory line could be drawn, a commission would arbitrate. Existing alliances the Czechs had with France and Russia would be dissolved. Chamberlain finished speaking with evident self-satisfaction now that they had an agreement.

Hitler then dropped the bombshell. "Ja, es tut mir leid, aber das geht nicht mehr." (Yes, I am very sorry, but that is no longer possible. )

Chamberlain sat up with a start, his face flushed with surprise and anger. He protested. He had taken his political life in his hands to get this agreement and had even been booed on his way to the airport in London. Unmoved by Neville's message or manner, Adolf said the procedures were too slow. Germany must be allowed to occupy Sudetenland immediately. German occupation must precede any international supervision of the changeover. The plebiscite to determine demarcation lines must also occur under Nazi military rule. Demands made by Poland and Hungary against Czechoslovakia should be settled at this point as well.

Chamberlain, while shaken by Hitlerís obvious preference for iron and blood did not concede defeat. Later he recounted to Ida that he returned to his hotel across the Rhine with his mind "full of foreboding to consider what I was to do." The following day he continued his attempt to persuade Hitler to accept a compromise. Hitlerís retort was to shorten the timeline and demand cession of the territory by September 28 - four days hence. During their meeting news was brought in that the Czechs had ordered mobilization, Hitler said that settled the matter.

|

|

Taught with Tense Times |

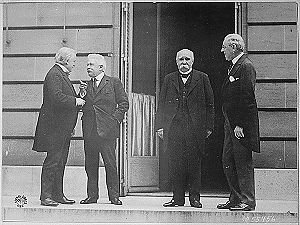

Following the end of World War I, the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire left a litter of small nationalities, all of which rushed to be recognized as countries by the Allied Commission, which comprised the leaders of the United States, United Kingdom, France and Italy. They set themselves the task of remaking the map of Europe.

|

|

From the left |

Foremost among those clamering for statehood, were the Czechs. Their glorious past, their deep love of freedom and their sobre, industrious virtues were impressive credentials. By 1919, the Czechs had acquired most of the territory with which they wanted to create their new nation. It included the Austrian provinces of Bohemia, Moravia and Silesia, as well as the Hungarian province of Slovakia. Czech troops had also moved into the German-speaking borderlands, where Bohemia met Austria in the south and Germany in the north. Czechoslovakia and Poland both wanted Teschen, a prized possession because of its coalfields and major railroad junction. When they could not agree on a compromise, the Allied Commission divided it between the two, resulting in the former friends becoming enemies.

The Commission had created a state whose numerous nationalities were seemingly all filled with hatred one to the other. Out of Czechoslovakiaís 14 million people, 3 million were German, 700,000 were Hungarian and a number were Poles. The Czechs and Slovaks made up the other two thirds of the country and no love was lost between them. The Czechs dominated the national government and refused to grant the Slovaks the autonomy they had been promised. Britain's Lloyd George expressed concern about creating a country comprised of so many nationalities, but the Czech leader, Edvard Benes, said it would work, because they intended to create something comparable to Switzerland's canons to accommodate the needs of each nationality. This was never done.

In a speech in Berlin on September 26 1938, just a few days before Czechoslovakia was carved up by the Munich Agreement, Hitler argued that the country was built on a lie: namely on the invented notion that there was such a thing as a Czechoslovak nation. He argued that the Czechs, and in particular Edvard Benes, had thought up the concept as an artificial way of increasing the influence of the Czechs. Hitler accused the Anglo-Saxon statesmen of not even thinking it necessary to check whether this claim was true. If they had, he argued, they would have found out straightaway, that there was no such thing as a Czechoslovak nation, but that there are Czechs and Slovaks and the Slovaks donít even want to have anything to do with the Czechs. Bitterness between Czechs and Germans had existed for hundreds of years, the hostility between the two extending as far back as the fourteenth century. Wenceslas IV, who acceded to the Kingdom of Bohemia in 1378, was assailed posthumously by bad press from German chroniclers.

Some historians have asked whether there wasn't an element of truth in Hitler's argument?

One Czech's response.

"Well, this is a very difficult question. Most people now in our country, as well as in Slovakia, would agree that there are two nations. But let us talk about the idea as expressed by Masaryk. He was among those that believed that nations are not, as Hitler did, a product of ethnic roots, but that nations are a programme that you daily vote for. And he very much hoped, and I think this was his deepest political conviction,that you can shape society by intentions.

"We have to say that the idea of one nation, of the Czechoslovak nation, can be traced back to the 19th century, so it was not Bene's or Masarykís invention in 1918. And I would like to add one more thing. The Slovak nation was heavily under-developed at that time. The elite of that nation was very restricted and the majority of that elite considered themselves to be Czechoslovaks. So we can definitely see that there were arguments for the unity of the Czechoslovak nation at that time, but history, as Professor Musil said, proved that they were wrong."

The Sudeten Germans were traditionally very nationalistically orientated and suddenly these independent-minded people became a secondary part of the new country. Nevertheless, as far back as 1926, the majority of the German inhabitants of the country discovered that there were positive aspects to their existence in this created country. They learned of liberal democracy and they receoved economic advantages to being an organic part of a country. One German author, Johann Wolfgang BrŁgel, who wrote about the interaction between Czechs and Germans, said that he preferred to support Czech democracy before supporting German nationalism. Unfortunately, others disagreed, one of whom was Konrad Henlein, a leading Sudetenlander.

While some Germans still remain convinced that their living conditions in Czechoslovakia were unbearable, there are many Czechs who say that this was not true, because between the wars, Czechoslovakia was one of the last democracies in Central Europe, which meant that their basic rights were secured. There are those who believed the Sudeten Germans were fairly well treated, but were chronically discontented, just as the Czechs had been when they were part of the Dual Monarchy. Nazis gained a foothold within the Sudetenland, when ethnic Germans there continued to complain, believing with some justification, that the countryís economic policies favoured the Czech majority. As a result, elections in 1938 saw around 80 per cent of Germans voting for Konrad Henleinís Sudeten German Party, On 1 October 1933, Henlein created a new political organization - the Sudeten German Home Front (Sudetendeutsche Heimatfront), which professed loyalty to the Czechoslovak state, but actually championed decentralization. It absorbed most former German Nationals and all Sudeten Nazis.

|

|

Konrad Henlein |

|

|

Sudeten Flag |

|

|

Sudetenland |

The twenty per cent of the Sudetendeutsche that didnít vote for the Nazis is often conveniently forgotten in Czech history. The clear trend, however, put the very territorial integrity of Czechoslovakia at risk. Konrad Henlein met with Hitler in Berlin on 28 March 1938 and was instructed to raise demands that were unacceptable to the Czechoslovak government. In the Carlsbad Decrees issued on 24 April, the Sudetenland German Party [SGP] demanded complete autonomy for Sudetenland, which he said was the people's will and which had been violated by Czechs since 1919.

As the political situation worsened, security in Sudetenland deteriorated. The region became the site of small-scale clashes between young SGP followers (equipped with arms smuggled from Germany) and police and border forces. In some places the regular army was called in to pacify the situation. Nazi German propaganda accused the Czech government and Czechs of nflicting iatrocities on innocent Germans, some of which did occur, but in retaliation for unarmed Czech troops being murdered by Sudeten German demonstrators from the first days of occupation. At least 24 petitions and motions were filed to the League of Nations in Geneva, accusing the Czech Government of violating the Treaty for the Protection of Minority Rights of 1922. However, due to Benes's influence within the League of Nations, all of them went unanswered.

In August, British Prime Minister, Neville Chamberlain sent Lord Runciman, (19 November 1870 - 14 November 1949) a representative of the British Government to Czechoslovakia to see if he could assist the parties - Benes and Henlein - to reach a compromise agreement that would forestall Hitler's hurry to absorb Bohemia. Henlein was disinterested and only met briefly with him. Benes was equally difficult, unwilling to change much of what offended the Sudentendeutche. A frustrated Runciman's mission resulted in a devastating report about Czech inability to respect minority rights He accused the Czech Government of violating basic rights and of lacking any readiness for a solution on an adequate scale. Hitler ordered Henlein to hold out no matter what he was offered.

"It is a hard thing to be ruled by an alien race; and I have been left with the impression that Czechoslovak rule in the Sudeten areas for the last twenty years, though not actually oppressive and certainly not 'terroristic', has been marked by tactlessness, lack of understanding, petty intolerance and discrimination, to a point where the resentment of the German population was inevitably moving in the direction of revolt. The Sudeten Germans felt, too, that in the past they had been given many promises by the Czechoslovak Government, but that little or no action had followed these promises. Even as late as the time of my Mission, I could find no readiness on the part of the Czechoslovak Government to remedy them on anything like an adequate scale. All these and other grievances, were intensified by the effects of the economic crisis on the Sudeten industries, which form so important a part of the life of the people. Not unnaturally, the Government was blamed for the resulting impoverishment. Czech officials and Czech police, speaking little or no German, were appointed in large numbers to purely German districts; Czech agricultural colonists were encouraged to settle on land confiscated under the Land Reform in the middle of German populations; for the children of these Czech invaders Czech schools were built on a large scale; there is a very general belief that Czech firms were favoured as against German firms in the allocation of State contracts and that the State provided work and relief for Czechs more readily than for Germans. I believe these complaints to be in the main justified. Even as late as the time of my Mission, I could find no readiness on the part of the Czechoslovak Government to remedy them on anything like an adequate scale ... the feeling among the Sudeten Germans until about three or four years ago was one of hopelessness. But the rise of Nazi Germany gave them new hope. I regard their turning for help towards their kinsmen and their eventual desire to join the Reich as a natural development in the circumstances."

The Sudeten Germans protested but to no avail, until Hitler decided to exploit the tensions between the dominant Czechs and the German-speaking inhabitants of the Sudetenland. While he spoke of reuniting the Sudetendeutsch with the Reich, they had never actually been part of Germany. These frontier dewellers in the German-speaking areas of Sudetenland, which ringed Czechoslovakiaís northern, western and southern frontiers with Germany, had been part of the dominant ethnic group in the Austro-Hungarian Empire and they resented Czech-rule from the start.

Fall Grun - Operation Green, was Hitlerís codename for the destruction of Czechoslovakia. He anticipated but a brief, local conflict, resulting in the return of the Sudeten Germans to Germany and the absorption into the Reich of a large section of what remained of the country. He was prepared to share the remainder of that truncated nation with Czechoslovakiaís covetous neighbours, Poland and Hungary, who had been told by Hitler, that if they "wished to share in the meal, they would have to help with the cooking."

Despite the fact that France and Russia had an alliance with Czechoslovakia, Hitler was certain they would not come to the aid of the beleaguered nation. At best Russia was an unreliable ally and France, fearful of the military might of German, refused to act without Britainís active involvement. Britain was the key to any conflict, but Neville Chamberlain declared his country could not commit itself to backing French action in support of Czechoslovakia. Britain was not prepared to fight a war, nor, said Neville, would the Dominions. In the face of a great deal of opposition from wide sources inside and outside parliameent, Chamberlain, as Chancellor of the Exchequer, had brought in a budget in 1936 that included a plan for rearmament. He dreaded the ncessitiy of doing so and complained, "If it wasn't for Germany, we would be having such a wonderful time just now. What a frightful bill do we owe to Master Hitler, damn him." He believed,however, taht appeasement and rearmament were sides of the same coin. The budget was denouced by many in the country as warmongering. Chamberlain did realize that ultimately, fear of force was the only remedy.

Hitlerís certainty of France and Britain's reluctance to back Czechoslovakia militarily was bolstered during the summer of 1938 when they sought to appease him by pressing the Czech government into make concessions. As he became more bellicose, tensions became tauter.

France's Premier …douard Daladier, a large, heavy set man with a florid face, was known as "the bull of Vaucluse" because of his thick neck and large shoulders. He was a former teacher who had earned his officer's chevrons serving in the trenches during World War I. Now he was torn between dishonouring his countryís treaty obligations or going to war. Despite having no illusions about Hitler's ultimate goals, he was faced with a defeatist military and public, all naturally very traumatized by France's blood bath in the first World War. Daladier deferred to Chamberlain, who set out to make the best bargain he could with Hitler.

Churchill, who vigorously opposed appeasement of Hitler, believed Britainís choice was between war and shame. He feared Chamberlain would choose shame, following which war would come. German aggression, he said, should be condemned, not countenanced. Britain should tell Germany that if she set a foot into Czechoslovakia, "we should at once be at war with her." Winstonís words were not well received. His perennially pessimistic prognostications were unpopular. He was considered by many to be a warmonger, reliving the life of his illustrious ancestor, Duke of Marborough. As his lonely voice continued to cry out of the coming catastrophe, he was harshly criticized. He even came close to being censured by his own constituents, the voters of Epping. In an article in the Daily Telegraph on 15 September, Churchill decried the loss of the military might of Czechoslovakia. If the Czechs were not pressured and persuaded to concede by France and Britain, they would have resisted the Reich invasion and inflicted heavy casualties on the assaulting Germans, for which the world would hold them blameless. His criticism of the course Chamberlain had followed was drowned out by the chorus of cheers that greeted Chamberlainís relentless pursuit of peace, no matter the price. Winston's was a voice in wilderness. Nineteen thirty-eight was a dark year for Churchill.

Some historians argue that Winston was wrong to counsel war in September 1938. The year Chamberlain purchased at the price of Czechoslovakia allowed Britain to gain the much-needed time to prepare for the coming conflict. Dour Air Marshal Sir Hugh Dowding stressed the critical need for more planes and pilots for the Battle of Britain, which ultimately resulted in "much being owed by so many to so few." Even George VI cheered Chamberlainís audacious act, calling it "a stroke of genius." He added, "I really cannot understand our old friend Winston Churchillís attitude, which is hardly worthy of the brilliant and experienced politician he is." The former King, Edward VIII, now Duke of Windsor, was an ardent appeaser who congratulated Chamberlain for doing what he had earlier proposed doing himself: fly to Germany to serve as a mediator and "expostulate with Hitler."

|

|

Chamberlain, Hitler and Hitler's Interpreter, Schmidt |

After they finished tea, Hitler asked what procedure Chamberlain proposed. Chamberlain replied that if convenient, he would prefer a tete-a-tete. Whereupon Hitler arose and walked up stairs through a long room containing pictures of nudes, until they reached his own room. It was completely bare of ornament. There was not even a clock, only a stove, a small table with 2 bottles of mineral water (which he never offered to Chamberlain), three chairs and a sofa. There they sat and talked for three hours.

Hitler animatedly outlined his views on racial unity and his commitment to return all Germans back into the Reich. Having successfully incorporated the seven million Austrians, he was now fixated on doing the same for the three million German-speaking Sudetens. Chamberlain interrupted his harangue to inquire whether this was his only demand. Hitler responded that when this was achieved and the other minorities seceded from Czechoslovakia, it would be so small, he would not be bothered about it. Schmidtís version of this was somewhat different: "Czechoslovakia would, in any case, cease to exist after a time."

Despite Chamberlainís obliging attitude, Hitler was dismayed, for it forestalled his fixed plan to annex the whole of Czechoslovakia. Hitler glared as he declared he would demand nothing less than the annexation of the Sudeten territory. "I am determined to settle it; I donít care whether or not there is a world war." To the shocked astonishment of the German interpreter, - for no one in the Reich would ever have dared to interrupt der Fuhrer - Chamberlain interjected angrily, "If I understand you correctly then, youíre determined in any event to proceed against the Czechs. Why have you had me coming to Berctesgaden at all? Apparently, itís all pointless." Unless Hitler had something further to suggest, Chamberlain said, it seemed nothing else could be done.

After a tense silence and to Schmidtís even greater incredulity, Hitler retreated. His whole demeanor changed and in a calm, quiet voice, he said that if Chamberlain could assure him that the British Government accepted the principle of self-determination for the Sudetendeutsche, he was prepared to discuss how it might be accomplished. Seizing at Hitlerís seemingly conciliatory change of attitude, Chamberlain quickly assured Adolf that he personally could see no reason why the Sudeten Germans should not be in the Reich. However, consultations with others would be necessary, after which he agreed to return for a further meeting. Hitler, feigning regret that the Prime Minister had to make two trips, graciously agreed to meet him halfway in the vicinity of Cologne.

The next days were spent applying pressure to the Czechs to acquiesce to their countryís dismemberment. President M. Benes, whom Churchill called ĎBeansí, was awakened from sleep to receive the Anglo-French ultimatum: the Sudetenland must be annexed to Germany. He said he had no alternative but to submit to their pressure. Five years earlier, Benes had publicly stated "that no country could be forced by anyone to revise its frontiers, and that anyone who attempted it in the case of Czechoslovakia would have to bring an army along. " He learned rather late that, as Hitler observed in Mein Kampf, "An alliance whose object does not include the intention to fight is meaningless." To compensate Benes for his willingness to capitulate, his two erstwhile allies, Britain and France, now pledged to defend from further German aggression what was left of his country. Their word and warrant were worthless.

On his return to the Reich, Chamberlain was welcomed at Cologne airport by a galaxy of dignitaries and his passage through streets decorated with swastikas and Union Jacks was greeted by thousands of cheering, joyful Germans. On Thursday 22 September, Chamberlain and Hitler met at Godesberg, a quiet, spa-resort town on the Rhine, just outside Bonn.

|

|

Bad Godesberg, located along the hills and cliffs of the west bank of the Rhine river, in west central Germany. |

|

|

The Dreesen Hotel, September, 1938 |

|

|

The Dreesen Hotel 2011 |

The Dreesen Hotel is situated along one of the most beautiful parts of the River Rhine in Bad Godesberg on the outskirts of Bonn. The site of the second meeting of Chamberlain and Hitler, it was one of Adolf's favourite hotels.

|

|

Neville and Adolf entering the Dreesen Hotel |

|

|

Neville and Adolf in the Dreesen Hotel |

Chamberlain was in fine fettle as he entered the hotel, for he believed he had secured a deal that would give Hitler what he wanted without the shedding of a drop of anyone's blood. He nnounced proudly at their meeting that he had gotten agreement to the terms from the British and French governments and had forced the Czechs to accept them by an Anglo-French ultimatum. An exaltant Chamberlain announced that the Sudetendeutsche districts would be transferred to the Reich and where no satisfactory line could be drawn, a commission would arbitrate. Existing alliances the Czechs had with France and Russia would be dissolved. Chamberlain finished speaking with evident self-satisfaction now that they had an agreement.

Hitler then dropped the bombshell. "Ja, es tut mir leid, aber das geht nicht mehr." (Yes, I am very sorry, but that is no longer possible. ) Chamberlain sat up with a start, his face flushed with surprise and anger. He protested that he had taken his political life in his hands to get this agreement. He had even been booed on his way on his way to the airport in London.. Adolf was unmoved by either his manner or his message. He said the procedures were too slow. Germany must be allowed to occupy Sudetenland immediately. German occupation must precede any international supervision of the changeover and the plebiscite to determine demarcation lines must also occur under Nazi military rule. Demands made by Poland and Hungary against Czechoslovakia should be settled at this point as well.

Chamberlain, while shaken by Hitlerís obvious preference for blood and iron did not concede defeat. He recounted later to Ida, that he returned to his hotel across the Rhine with his mind "full of foreboding to consider what I was to do." The following day he continued his attempt to persuade Hitler to accept a compromise. Hitlerís retort was to shorten the timeline and demand cession of the territory by September 28 - four days hence. When during their meeting news was brought in that the Czechs had ordered mobilization, Hitler said that settled the matter.

|

|

Tense Times |

A frustrated Chamberlain, unable to conceal his indignation, objected to Hitlerís new demands. In response Hitler's sole grudging gesture, "to one of the few men for whom I have ever done such a thing," was to postpone the German invasion of the tiny republic until October 1st. Once the Sudetenland had been acquired, it would, he pledged, be his last territorial demand in Europe.

Chamberlainís fears and frustrations were not assuaged one bit by the telegram he received from Lord Halifax, informing him that public opinion was turning against selling out the Czechs. Halifax advised that he inform Herr Hitler, that if he rejected a peaceful solution, he would be committing an "unpardonable crime against humanity." Even the humourless Chamberlain must have smiled sardonically at this preposterous suggestion. Instead of compromising, Hitler had dictated new terms to which Chamberlain, :totally surrendered." Following an early morning meeting between him and Hitler, to which Paul Schmidt was the only witness, Schmidt recorded that they took, "leave of one another in a completely friendly manner after having had with my assistance, an eye to eye conversation." "Between us there should be no conflict," Hitler said to Chamberlain.

|

|

Chamberlain was convinced Hitler's double handshake meant a true trust. |

In London Chamberlain had a difficult time convincing the Cabinet to agree to Hitlerís latest demands. They now found the terms in the Godesberg Memorandum unacceptable. The consensus appeared to be that the Czechs should not be pressured into accepting an ultimatum tantamount to a military defeat. Hitlerís new terms presupposed he had won a war without having to fight it. Public opinion was harder to gauge, but a loud and influential body of opinion argued against the betrayal of Czechoslovakia.

Chamberlain decided to make, what he described to his sisters as, "the last desperate snatch at the last tuft of grass on the very edge of the precipice." He telegraphed Hitler seeking one further meeting at which final details could be settled for the transfer of Sudetenland to the Reich. He also appealled to Mussolini to preserve the peace by intervening with Hitler. The Italian dictator, grabbing at the chance to avoid war for which Italy was totally unprepared, urged Hitler to accept Chamberlainís proposal. "I feel certain," he said, " you can get all the essentials without war and without delay."

On the morning of the 28th - Black Wednesday - war appeared to be hours away. Chamberlain entered the House of Commons to cheers "from all parts of the House" to give "a chronological account of events." It was listened to "in dead silence," and when he came to recent events, tension rose even higher. An hour into his speech, a disturbance arose long the front bench, as two pieces of paper were brought in by Cadogan. They were handed to Sir John Simon, a close associate of Chamberlain, who interrupted the Prime Minister's speech by tugging at his sleeve. Chamberlain was heard to ask, "Shall I tell them?" Simon whispered, "Yes." In one of the most dramatic moments the Commons' chamber has ever witnessed, a hush fell over the House. All eyes were riveted on the Prime Minister, the scene described by one historian as "a piece of stage management." "Herr Hitler has just agreed to postpone his mobilisation for twenty-four hours to meet me in conference with Signor Mussolini and Daladier at Munich on the morrow." Government members cheered their approval and were joined by the Opposition after receiving Atlee's approval. "It was a piece of drama that no work of fiction ever surpassed." Some historians say Churchill and a few other anti-appeasers remained seated. As the Prime Minister left the chamber, Churchill murmured , "You were lucky," shook his hand and wished him God's Speed.

|

|

Neville Chamberlain Broadcasting to the Nation |

Meanwhile back in Berlin on the afternoon of Tuesday, 27 September, a martial parade of a mechanized division with full field equipment rumbled through the streets under the eyes of the Fuhrer. Unlike the ecstatic, public display of excitement and enthusiasm that greeted a similar scene in 1914, there was sullen silence from the crowds. Many turned their backs and disappeared into the subway rather than look on. Their behaviour made it all too clear to Hitler, that he would be forced to confer rather than fight. Bad news multiplied when word arrived that the British fleet was being mobilized.

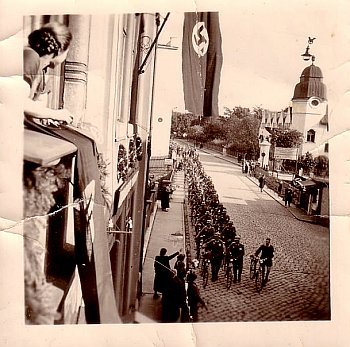

|

|

"Now we have him." |

On Thursday, 29 September, the Prime Minister left for Munich. The entire Cabinet came to the airport to see him off as "a pleasant surprise."

At Heston that morning, Chamberlain put it this way. "When I was a little boy, I used to repeat, if at first you donít succeed, try, try, try, try again. That is what I am doing. When I come back, I hope I may be able to say, like Hotspur in Henry IV, Part, to pluck from this nettle danger, this flower, safety."

On his way to the Fuhrerhaus, Chamberlain was driven past cheering crowds in an open-topped car through the streets of Munich with the German foreign minister Joachim von Ribbentrop next to him. Hitler was infuriated when he learned that the huge crowds had hailed Chamberlain as the hero of the hour. To shouts of Heil Chamberlain, Neville nodded and waved, astounded by the friendly fervour of their greeting. Der Fuhrer was beset by jealousy at the intensity of their welcome and dejected at the apparent apathy of his people toward the prospect of war. They were not ready for the "first-class tasks" Hitler meant to set them.

|

|

German Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop leading the Lamb to slaughter. |

|

|

: Ribbentrop looks on as Hitler and Chamberlain Chit-chat through Schmidt |

|

|

Mussolini was unimpressed with Chamberlain. |

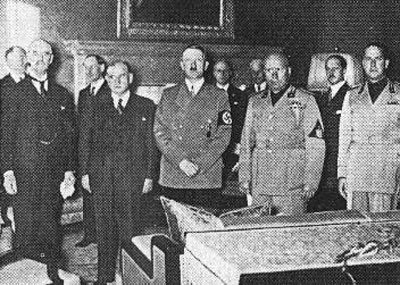

The heads of government of Britain, France, Italy and Germany met in Munich at 12:30 p.m. on 29 September in the newly built, spacious, red-columned salon on the first floor of the Fuhrerhaus. It was a classical edifice on the Konigsplatz. Its cream and pink marble Doric faÁade was interrupted by a huge bronze eagle with wings outstretched.

|

|

Fuhrerbaus Then |

|

|

Fuhrerbaus Now |

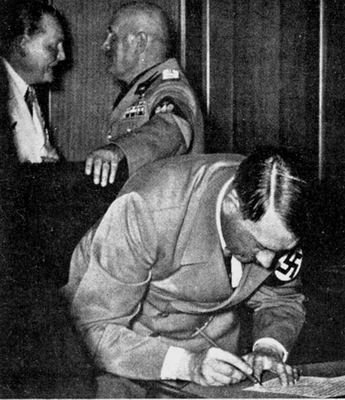

The leaders sat around a massive fireplace in armchairs, an arrangement not conducive to business. The hastily arranged conference lacked organization. There was no chairman, there was no a set agenda and no minutes were taken. Progress was slow because the general discussion broke down into individual arguments and general conversation. Difficulties with translations added to the confusion. Hitler, pale, excited and handicapped by his inability to speak any other language but German, leaned a good deal on Mussolini, who seemed more at ease than anyone else. With breaks for lunch and dinner, the conference lasted fourteen hours. By 2: a.m. on the 30th; the deal was done. It was symbolic of the barrenness of the business, that when Hitler dipped his pen into the inkpot it came up empty. The proposal was hammered out by Hermann GŲering and Benito Mussolini and presented to Chamberlain and French Prime Minister …douard Daladier. Czechoslovakia was not invited to the talks.

|

|

The MunchKins |

|

|

Hitler signs while conspirators crow in the background. |

|

|

Chamberlain Signs |

|

|

Mussolini Signs |

|

|

All Proudly Preen (except Daladier) |

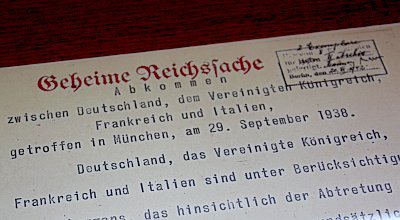

Agreement concluded at Munich, September 29, 1938, between Germany, Great Britain, France and Italy GERMANY, the United Kingdom, France and Italy, taking into consideration the agreement, which has been already reached in principle for the cession to Germany of the Sudeten German territory, have agreed on the following terms and conditions governing the said cession and the measures consequent thereon, and by this agreement they each hold themselves responsible for the steps necessary to secure its fulfilment:

(1) The evacuation will begin on 1st October.

(2) The United Kingdom, France and Italy agree that the evacuation of the territory shall be completed by the 10th October, without any existing installations having been destroyed, and that the Czechoslovak Government will be held responsible for carrying out the evacuation without damage to the said installations.

(3) The conditions governing the evacuation will be laid down in detail by an international commission composed of representatives of Germany, the United Kingdom, France, Italy and Czechoslovakia.

(4) The occupation by stages of the predominantly German territory by German troops will begin on 1st October. The four territories marked on the attached map will be occupied by German troops in the following order:

The territory marked No. I on the 1st and 2nd of October; the territory marked No. II on the 2nd and 3rd of October; the territory marked No. III on the 3rd, 4th and 5th of October; the territory marked No. IV on the 6th and 7th of October. The remaining territory of preponderantly German character will be ascertained by the aforesaid international commission forthwith and be occupied by German troops by the 10th of October.

(5) The international commission referred to in paragraph 3 will determine the territories in which a plebiscite is to be held. These territories will be occupied by international bodies until the plebiscite has been completed. The same commission will fix the conditions in which the plebiscite is to be held, taking as a basis the conditions of the Saar plebiscite. The commission will also fix a date, not later than the end of November, on which the plebiscite will be held.

(6) The final determination of the frontiers will be carried out by the international commission. The commission will also be entitled to recommend to the four Powers, Germany, the United Kingdom, France and Italy, in certain exceptional cases, minor modifications in the strictly ethnographical determination of the zones which are to be transferred without plebiscite.

(7) There will be a right of option into and out of the transferred territories, the option to be exercised within six months from the date of this agreement. A German-Czechoslovak commission shall determine the details of the option, consider ways of facilitating the transfer of population and settle questions of principle arising out of the said transfer.

(8) The Czechoslovak Government will within a period of four weeks from the date of this agreement release from their military and police forces any Sudeten Germans who may wish to be released, and the Czechoslovak Government will within the same period release Sudeten German prisoners who are serving terms of imprisonment for political offences.

Munich, September 29, 1938.

|

|

Actual Munich Agreement (German) (Originals in English and German only. Others all copies. ) |

|

|

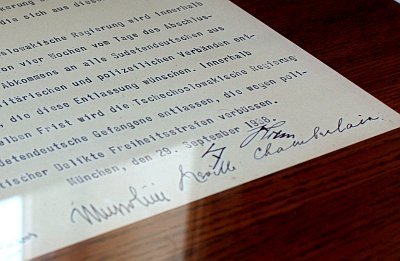

Signed, Sealed and Delivered |

The Munich Agreement appeared to be a slight improvement over the ultimatum issued at the Godesberg summit. Instead of the Germans storming into the Sudetenland on October 1, the takeover of the Sudetenland by Hitlerís Wehrmacht would be spread over ten days. An international commission would supervise the absorption of the German-speaking areas into the Reich and the plebiscites to be held in the affected areas. Later as a self-satisfied but badly deluded Chamberlain sat down for lunch, he complacently patted his breast-pocket and said, "Iíve got it."

|

|

Claretta Petacci, Mussolini's mistress, kept a massive diary that provided a devastating portrait of duce. |

Mussolini was pleased with the meeting. The diary of his mistress, Claretta, revealed these comments by Mussolini about Munich. He believed "the treaty" (Treaty of Munich) had gone well. He thought Daladier was a "nice man" and that Chamberlain for an elderly man was really "admirable." Here was a man almost 70, yet zealously working into the wee hours. "I had prepared everything. They would not have known were to begin." He said that he alone could speak the requisite foreign languages and it was thus proper for Chamberlain and Daladier to address him as duce throughout the proceedings. He commented it was true that Hitler would sometimes get "threateningly cross," but he let Mussolini calm him. So, they found Nazis-Fascist "peace and victory".

On the other hand, Hitler, despite having carried off a coup without cost, believed his triumph was dearly bought. He ranted that that damned Chamberlain, had "meinen Einzug in Prag verdorben" (spoiled my parade into Prague).

|

|

"He really, really likes me," said the duce on his return home. |

This supported Mussolini's view that the fuhrer was, "always a little in awe of me."

The Czechs played no part in the conference concocted to fix their fate. Chaberlain and Daladier met with the Czech representative, Mastny, waiting at the British hotel. They were told to sign their own death warrant, by which they were to evacuate the whole Sudeten region, including their border fortifications, starting October 1 and be out by the 10th. Other territories were ceded to Poland and Hungary. Czechoslovakia lost roughly a third of its population and the Czech and Slovak halves were no longer contiguous. According to Mastny, Chamberlain "yawned continuously without making any attempt to conceal his yawns or his weariness."

The Czechs were to leave with only the clothes on their backs. Everything else was to be left behind - military arms and equipment as well as their personal possessions including household goods, furniture, horses and cows, for which there was no compensation by Germany. Churchillís description of this peace at any price, might well have been theirs at that tragic time. "Silent, mournful, abandoned, broken, Czechoslovakia receded into the darkness. She has suffered in every respect by her association with the Western democracies." Churchill's protrayal of the treaty was correct. The Munich Agreement has gone down in history as a byword for betrayal.

|

|

10 September, 1938: Benes Prepares Nation for Bad News |

"My fellow citizens, I am addressing you at a time of international crisis, the largest since the World War. These events have not only engulfed Europe, but also other parts of the world. At this critical moment, I am talking to you about us, about our standing in the middle of this anxious world. And I am talking to you all, Czechs, Slovaks, Germans and to other nationalities, and within this, to all groups, to all camps, to all positions"

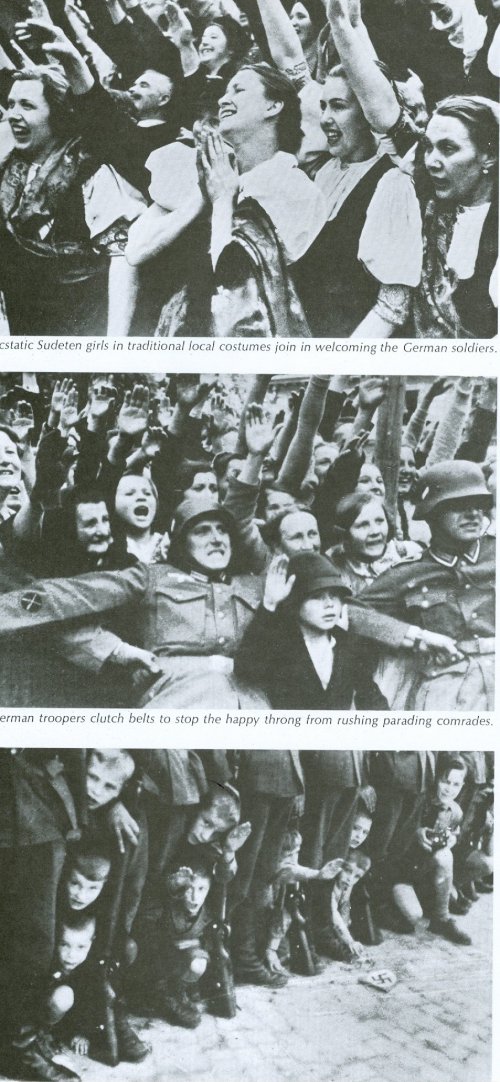

We learn afterwards that in September 1938, the Czechoslovak people were ready to fight. On September 23 there was a mobilization of forces and the people were excited that they were going to fight, because it was after months and years of political pressure from Germany and it was clear that the process was heading towards war. Troops were sent to the borders and Czech border fortifications were immediately consolidated. Concrete bunkers were placed on alert and barbed wire border posts were strengthened. If German troops were going to cross the steep hills along the border, it would not be without a fight. The show of resolve was short-lived, for without British, French and Russian forces to follow, the outcome was tragically predictable. The Czechs bowed to the inevitable, and German forces crossed into Sudeten Czechoslovakia largely unopposed. They were greeted not with force but with flowers, as joyous Sudetendeutsche welcomed Hitler as their saviour. With its impressive border defences penetrated, the rest of the country lay open to the onslaught of the Nazis hordes.

|

|

Delirious Sudetendeutsche - Sow the wind;reap the whirlwind. |

|

|

Hitler's Hordes |

|

|

Happy to greet Hitler's Hordes |

|

|

Hitler savouring the sights and the sounds of Sudetendeutche. |

|

|

Overcome by it all |

Having achieved a bloodless victory, Hitler then broke every aspect of the agreement. Plebiscites were never held. Two hundred and fifty thousand Germans were still left in Czechoslovakia and eight hundred thousand Czechs remained in the land ceded to Germany. Czechoslovakia lost its system of fortifications, together with eleven hundred square miles of territory. In Germany relief was high that war had been avoided. Hitlerís reputation rose to new heights for having acquired so much for so little. Hitler did what he promised not to do: take what was left of the country in March 1939. Bohemia became a German colony, Ruthenia was taken by the Hungarians and Hitler allowed Slovakia to become a "free state" under German control .Czechoslovakia ceased to exist as a country.

Although "pleasantly tired" on the flight home, Chamberlain was flushed with victory. When he arrived at the airport, his fatigue was replaced with rapture at the reception he received. Delirious crowds showered him with greetings and gratitude. Good old Neville had kept the country out of war. Chamberlain related the events to his sister. "In the streets they were lined from one end to the other with people of every class, shouting themselves hoarse, leaping on the running board, banging on the windows and thrusting their hands into the car to be shaken."

In France even those who despaired at their country's betrayal of Czechoslovakia, could not help sharing the feeling of relief. War was a fearful thing, a horrid prospect for fathers and mothers haunted by the horror and havoc of WW I. They and their sons had been spared the blood-letting of another great conflict. Ashamed and devastated by what he'd done, Daladier returned to Paris fully expecting to be greeted by raging crowds and rotten eggs. Instead he was welcomed at the airport by cheering crowds. Turning to Leger, he whispered, "the bloody fools."

Within nine months, France had been beaten and forced to surrender. Daladier was arrested by France's Vichy government and put on trial for not adequately preparing France for the war she quickly lost. The country badly needed a scapegoat. He decided not to accommodate them. His spirited defence derailed the trial, for his clever arguments identified the army that had failed to fight as the culprit. Not wanting public dbate about the debacle that was the real reason for the country/s sudden and sad defeat, the trial was quickly discontinued. Daladier was imprisoned in Itter Castle, a small castle overlooking the village of Itter in the Tyrol Austria. It is known to have been the place of detention for a number of personalities and French General officers during the Second World War. Daladier spent the remainder of the war writing his memoirs, which were published by his son after Daladier's death in 1970. .

On Neville's return from Munich, he flourished the accord Hitler had signed and caught up in and carried away by the exuberance of the moment, Chamberlain made a claim that came back to haunt him. He hailed the Munich Agreement as enduring "peace with honour."

A more believable boast would have been that he brought Britain much-need time to prepare for the coming conflict with the Nazi state.

|

|

But a scrap of paper |

Later in the British House of Commons when Churchill said Munich meant Britain had "sustained a total and unmitigated defeat," he was howled down and assailed by an angry, emotional outburst of protest from many of the Members.

|

|

|

Rarely has a man's reputation been so dramatically transformed. Lauded as a peacemaker by delirious crowds, Neville was shortly to be reviled as the architect of appeasement.

It is well to remember that Chamberlain did not decide on his own to hand Hitler the Sudetenland. His mission was made with the strong approval from most colleagues in the Cabinet and on the urging of his military advisors. Their advice: forego onfrontation with the Fuhrer and convince the Czechs to conform. Britain, they cautioned, was not ready to rout Hitler militarily. War then could well have been catastrophic for the country. Time was needed to re-arm.

Chamberlain obliged and subsequently savoured the sight of wildly cheering crowds as he posed proudly with the King and Queen on the balcony of Buckingham Palace, The crowds roared until they were hoarse. A wave of euphoria swept the country and Downing Street was deluged with letters of praise and gifts gallore that included, flowers, fishing rods and umbrellas. Even the French were caught up in the gifting, the Paris-Soir offering him "a corner of French soil," where he could fish. The editor said, "there could be no more fruitful image of peace."

Time brought the, carnage and chaos of another war and with it the defamation of Neville's name, for Chamberlain is associated forever with a policy of craven appeasement. Providentially, the nation's honour was salvaged by Winston, the self-same warmonger, whose wearisome warnings of the terror and tumult to come had been derided aa delusional. France, unfortunately, had no such soul to save it's renown and ravaged reputation.

The next time the British got caught up in a frenzy of wild emotion, Winston was the one on the balcony beside the king and queen, cheered to the heights for having faced, fought and defeated the Fuhrer and his fiends.

|

|

Sudetenland then |

|

|

Sudetenland then |

|

|

Sudetenland now |

Finally on 8 May,1945 after all the chaos and killing, Churchill could say to Stalin, here at last was an end, "to the sacrifices and sufferings of the Dark Valley thorough which we have marched together."

Fast Forward Seventy Years and what do Czechs say today?

"I think that since that time, in Czech culture there is a strong frustration because we were the neighbour of Germany and we were the first who would be attacked. And the French thought that they were insured if they sold Czechoslovakia out because Hitler would want no more. But the Czechs and Poles knew that this was nonsense, because they knew that Hitler would want more. And that debate, seventy years on appears to be as lively as ever. In the newspapers you still can read the lively debate about whether we should have fought. And everybody has their own opinion. I think that there are quite a few people who believe that we should have fought, Of course it was obvious that we would lose because nobody would have helped us, not France, not Great Britain. But you would have had the possibility to fight and it is perhaps better to do that and to die fighting than die in a concentration camp."

While opinions on that issue may differ, it is with a far greater conviction that a vast majority of Czechs continue to feel that the Munich Agreement was a most shameful betrayal of their country by the Western powers. And it was this betrayal that led ultimately to a slow and perhaps even understandable shift towards the promise offered by the Soviet Union in the post WWII climate. After the horrors unleashed by the Munich Agreement (or Munich Dictate in Czech), the later humiliation of the Bohemian and Moravian Protectorate and the partial redemption offered by the Czech assassination of German Reich Protector Reinhard Heydrich in 1942, the horrors were far from over. As the liberation from Nazi rule came, another dark, humiliating and hopeless chapter in Czech history was about to be unleashed, and again the country found itself the helpless target of a larger power.

Original Munich agreement to go on display in Prague next month</p>

Tuesday, September 30, marks exactly 70 years since the signing of the Munich agreement, under which Czechoslovakiaís German-speaking territories were sliced off and handed to Hitler. The document was signed on September 30, 1938 by Britain, Germany, Italy and France. Just a week ago, Germany unexpectedly agreed to loan the original version of the document to the Czech Republic. It will go on display at Pragueís National Museum as part of a large exhibition commemorating 90 years since the foundation of Czechoslovakia. Ruth FrankovŠ spoke with the museumís historian Marek Junek, who says talks with Germany on borrowing the treaty lasted nearly a year: "When we met for the first time, they said that the document has never been abroad. They didnít know the concept of our exhibition and they were afraid that we would display the agreement in a negative way. But after a few meetings they finally agreed to loan the agreement to the Czech Republic."

A copy of the original Munich agreement is on display in the Czech Senate. "How did you persuade them to loan the agreement to Prague?"

"The first argument was that this is not an exhibition about the Munich agreement, but about the First Czechoslovak Republic and that the Munich events are just a part of the whole exhibition. We also promised to display the document in circumstances that will be historically objective."

"What about the other versions, the British, French and Italian?"

"The Munich agreement was signed only in German and English versions, so the original documents are in Berlin and London. Our colleagues from the government archives in London have already promised to lend us the document. The French and Italian versions are copies that were translated soon after the Munich meeting but they are not original pieces of the agreement."

"We would of course like to exhibit all four pieces of the agreement, but our French colleagues, who lost the document during the WWII, are they now trying to find it. Our Italian colleagues didnít want to loan us the treaty at first but they changed their mind when they found out that the Germans agreed with the loan."

"Finally, how important is it for the National Museum to have the Munich agreement exhibited?"

"I think it is very important because the document will be part of the exhibition about the Czechoslovak Republic founded in 1918 and it is a very important part of our history. The original copies of the Munich agreement will be on display at the National Museum between October 28 and March 15. In the mean-time, a copy of the document went on show at the Czech Senate on Sunday."

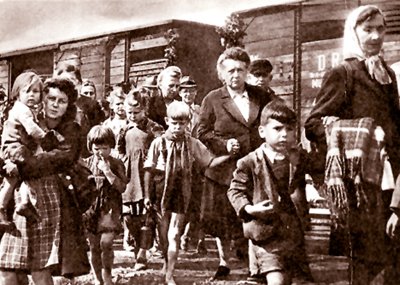

After the end of World War II, the Potsdam Conference in 1945 determined that Sudeten Germans would have to leave Czechoslovakia . As a consequence of the immense hostility against all Germans that had grown within Czechoslovakia due to Nazi behavior, the overwhelming majority of Germans were expelled, many violently. According to the Wall Street Journal under date of 12.04.96, the Germans were loaded onto freight trains and deported to Germany along with the ethnic German minority in the Sudetenland region.

|

|

Expulsion of Germans from Sudetenland |

Disagreements and difficulties have delayed the signing of a reconciliation treaty between the two countries, which is intended to lay their past war grudges to rest. Some of the Germans who were expelled want an apology from the Czechs for their ethnic cleansing of some three million Germans. Other Germans want to return home [i.e. to the Sudetenland] and receive compensation for the property their families were forced to leave behind in 1946. The Czechs say they have never received reparations from Germany for the Nazis' crimes, and if the Germans won't pay, they won't say sorry. The Czech Republic has requested admission to EU and this complicates their application. Fortunately, goodwill prevailed, and the following treaty was signed in 1997.

Reconciliation Treaty

The Federal Republic of Germany and the Czech Republic today share common democratic values, respect human rights, fundamental freedoms and the norms of international law, and are committed to the principles of the rule of law and to a policy of peace. On this basis they are determined to cooperate closely and in a spirit of friendship in all fields of importance for their mutual relations.

At the same time both sides are aware that their common path to the future requires a clear statement regarding their past which must not fail to recognize cause and effect in the sequence of events.

The German side acknowledges Germany's responsibility for its role in a historical development which led to the 1938 Munich Agreement, the flight and forcible expulsion of people from the Czech border area and the forcible breakup and occupation of the Czechoslovak Republic.

It regrets the suffering and injustice inflicted upon the Czech people through National Socialist crimes committed by Germans. The German side pays tribute to the victims of National Socialist tyranny and to those who resisted it.

The German side is also conscious of the fact that the National Socialist policy of violence towards the Czech people helped to prepare the ground for post-war flight, forcible expulsion and forced resettlement.

The Czech side regrets that, by the forcible expulsion and forced resettlement of Sudeten Germans from the former Czechoslovakia after the war as well as by the expropriation and deprivation of citizenship, much suffering and injustice was inflicted upon innocent people, also in view of the fact that guilt was attributed collectively. It particularly regrets the excesses which were contrary to elementary humanitarian principles as well as legal norms existing at that time, and it furthermore regrets that Law No. 115 of 8 May 1946 made it possible to regard these excesses as not being illegal and that in consequence these acts were not punished.

Both sides agree that injustice inflicted in the past belongs in the past, and will therefore orient their relations towards the future. Precisely because they remain conscious of the tragic chapters of their history, they are determined to continue to give priority to understanding and mutual agreement in the development of their relations, while each side remains committed to its legal system and respects the fact that the other side has a different legal position. Both sides therefore declare that they will not burden their relations with political and legal issues which stem from the past.

Both sides reaffirm their obligations arising from Articles 20 and 21 of the Treaty of 27 February 1992 on Good-neighborliness and Friendly Cooperation, in which the rights of the members of the German minority in the Czech Republic and of persons of Czech descent in the Federal Republic of Germany are set out in detail.

Both sides are aware that this minority and these persons play an important role in mutual relations and state that their promotion continues to be in their common interest.

Both sides are convinced that the Czech Republic's accession to the European Union and freedom of movement in this area will further facilitate the good-neighbourly relations of Germans and Czechs.

In this connection they express their satisfaction that, due to the Europe Agreement on Association between the Czech Republic and the European Communities and their Member States, substantial progress has been achieved in the field of economic cooperation, including the possibilities of self-employment and business undertakings in accordance with Article 45 of that Agreement.

Both sides are prepared, within the scope of their applicable laws and regulations, to pay special consideration to humanitarian and other concerns, especially family relationships and ties as well as other bonds, in examining applications for residence and access to the labour market.

Both sides will set up a German-Czech Future Fund. The German side declares its willingness to make available the sum of DM 140 million for this Fund. The Czech side, for its part, declares its willingness to make available the sum of Kc 440 million for this Fund. Both sides will conclude a separate arrangement on the joint administration of this Fund.

This Joint Fund will be used to finance projects of mutual interest (such as youth encounter, care for the elderly, the building and operation of sanatoria, the preservation and restoration of monuments and cemeteries, the promotion of minorities, partnership projects, German-Czech -5- discussion fora, joint scientific and environmental projects, language teaching, cross-border cooperation).

The German side acknowledges its obligation and responsibility towards all those who fell victim to National Socialist violence. Therefore the projects in question are to especially benefit victims of National Socialist violence.

Both sides agree that the historical development of relations between Germans and Czechs, particularly during the first half of the 20th century, requires joint research, and therefore endorse the continuation of the successful work of the German-Czech Commission of Historians.

At the same time both sides consider the preservation and fostering of the cultural heritage linking Germans and Czechs to be an important step towards building a bridge to the future.

Both sides agree to set up a German-Czech Discussion Forum, which is to be promoted in particular from the German-Czech Future Fund, and in which, under the auspices of both Governments and with the participation of all those interested in close and cordial German-Czech partnership, German-Czech dialogue is to be fostered.